Severe floaters constitute Degenerative Vitreous Syndrome (DVS)

Robert E. Morris, MD

President, Helen Keller Foundation for Research and Education

Floaters are opacities that usually appear spontaneously in the field of vision of one or both eyes. They can intermittently obstruct central vision or appear as false objects moving in the peripheral visual field.

spontaneously in the field of vision of one or both eyes. They can intermittently obstruct central vision or appear as false objects moving in the peripheral visual field.

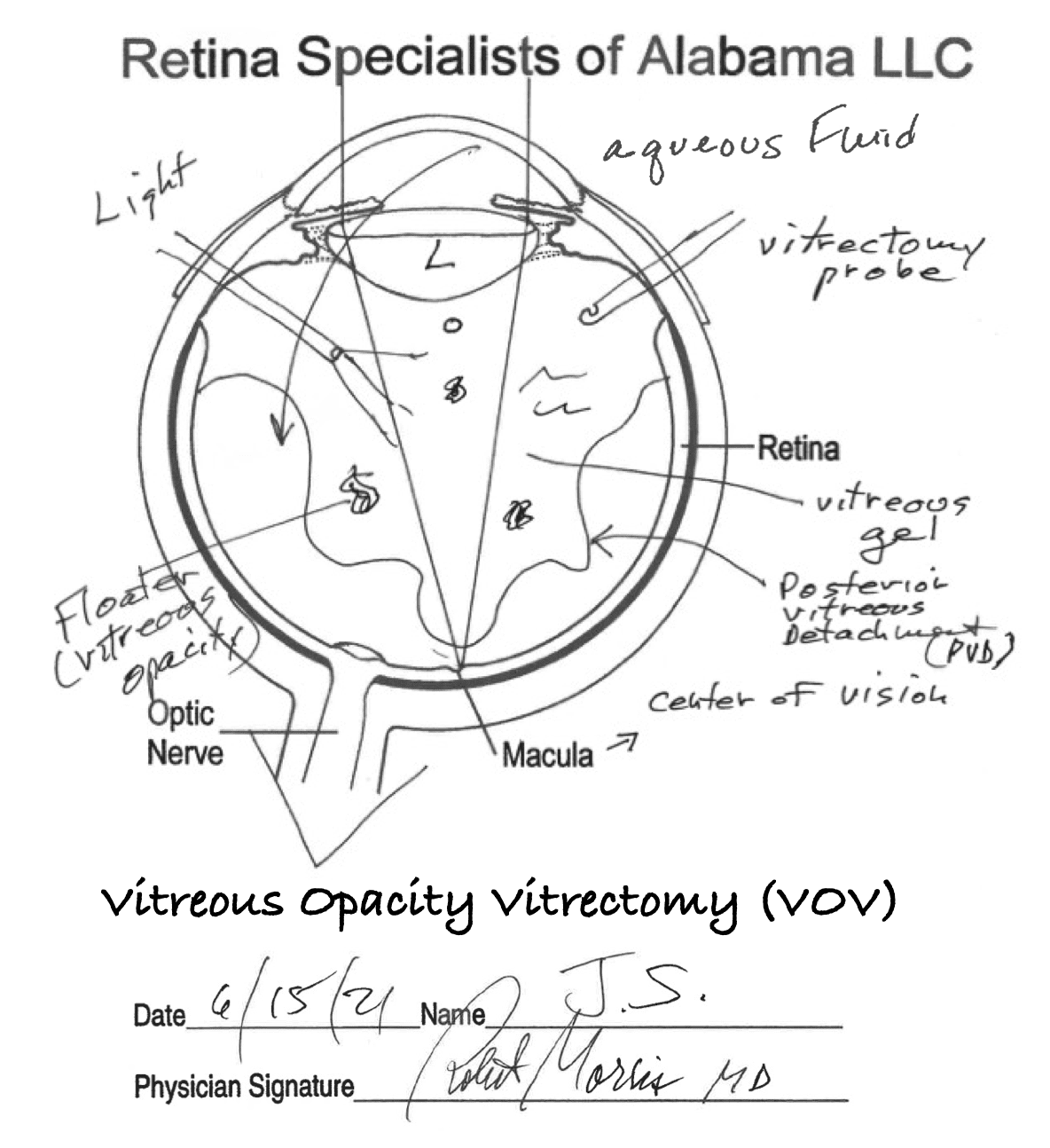

Floaters are in fact opacities in the vitreous gel that fills the eye posteriorly, between the lens and the retina (Figure). As a normal part of aging, the vitreous gel “shrinks” and spontaneously separates from the retina. It then begins to move with eye, head, or body movements, floating in the water-like fluid called aqueous that is constantly produced within the eye. Any opacities in the now-mobile vitreous gel cast shadows on the underlying retina and are seen as floaters of various sizes and shapes, easily mistaken for real objects, as one DVS sufferer describes here:

“I am continually seeing things that are not there. I move the hair that isn’t in front of my face. I search for the insect or small animal that never existed. I turn my head to speak to the person who didn’t approach me. And I stop to allow the mythical car to pass before I walk across the street.” MJK, DVS sufferer.

Although they are usually only a nuisance, if floaters are large or extensive, they can substantially interfere with tasks requiring continuously clear vision, such as safely walking down a flight of stairs. Diffuse vitreous opacity often accompanies floaters, so that DVS patients describe their vision as “hazy or gray, like seeing through a dirty window.” This causes glare in bright light environments and reduced sensitivity to low contrast items, such as newspaper print.

Physicians from Retina Specialists of Alabama (LLC), who are also research associates of the Helen Keller Foundation for Research and Education, developed the term “Degenerative Vitreous Syndrome” (DVS) to describe “the spontaneous occurrence in the aging vitreous of opacities that substantially interfere with daily visual activities.” We also developed the term Daily Visual Activities (DVA – reading, driving, recognizing faces, etc.) to help define visual disability, as opposed to the commonly used term Activities of Daily Living (ADL – eating, bathing, dressing, etc.) long used to define general disability. DVS distinguishes patients with extensive floaters from millions of persons with only occasional “nuisance” floaters whose vision is not substantially impaired.

Cataract extraction is now the most common surgery performed in the United States. It removes a cloudy human lens (cataract) and replaces it with an implanted clear lens that is typically better but thinner than the cataract. Because cataract extraction reduces the lens volume, thereby increasing the vitreous cavity volume, it may hasten vitreous movement and floater development in some patients. Or with improved vision after cataract extraction, one might actually see existent floaters better, so that they paradoxically become more bothersome.

The sudden appearance of new floaters should be investigated to rule out retinal tears that could lead to retinal detachment. But chronic, extensive floaters can be cleared by removing the vitreous gel (vitrectomy), since clear aqueous fluid automatically takes its place inside the post-vitrectomy eye. A detailed description of our technique of safest possible vitrectomy (Vitreous Opacity Vitrectomy, VOV), with a safety profile similar to cataract extraction, was published in Clinical Ophthalmology on June1, 2022.

Since my treatment of DVS patients began in 1994, I’ve collected the stories appearing below, written by DVS sufferers at my request, to help assess the need for vitrectomy. At that time the risks and morbidity of vitrectomy were substantially greater than currently, justifying intervention in only the most severe floater cases – such as those presented in our video that won the Buckler award at the 2007 annual meeting of the American Society of Retina Specialists.

This video marked the first time any ophthalmic organization had ever expressed approval of the then controversial removal of floaters by vitrectomy. Previously there had been minimal recognition of their significance, so that documentation of symptoms was important to explain intervention, and I began to collect the DVS patient stories.

The “floater stories” were so valuable for diagnosis and mutual understanding that I’ve continued this practice today. More than any “quality of life” questionnaire or measurement of contrast sensitivity or imaging, they’ve helped me understand how the relentless distractions of extensive floaters can be more bothersome than even the constant blur of cataract. Indeed, a 2019 study1 concluded that vitrectomy to remove floater opacities in the vitreous gel improved quality of life per health care cost even more than removal of cataract (lens) opacities, a long-accepted treatment.

In the early 1990’s I often heard or read floater stories from self-referred patients who found me after much searching. Since they could still slowly read the 20/20 line on the eye chart (one letter at a time, dodging the floaters), they were often told by multiple doctors “you don’t have a problem.” But for DVS sufferers, visual acuity tested by single letters, in an exam room, will not reflect their reduced functional visual acuity during daily visual activities. They were also frequently told, “you’ll get used to it”, or “the floaters will go away”, or “there is nothing that can be done”, or “there is an operation but it’s too risky.”

DVS patients were sometimes regarded as being psychologically “unbalanced” or as having unrealistic expectations. But they were predominately normal folks who simply wanted the continuously clear vision they once had, and that is now reasonably attainable with VOV, a special form of vitrectomy continually focused on least possible risk. In our experience, the risk of a serious problem during VOV performed by an experienced DVS surgeon is now less than 1%, although never zero. Nevertheless, as recently as 2015 one survey found that only 25% of vitreoretinal surgeons would remove floaters.2

Fortunately, most eye care providers have since seen DVS patients safely restored to continuously clear vision by experienced surgeons using modern vitrectomy technology. And negative responses to patients seeking help are rapidly giving way to appropriate referral of most DVS patients, from understanding eye care providers, to a vitreoretinal surgeon skilled in DVS diagnosis and treatment.

I typically asked DVS patients to write their story at the conclusion of our initial meeting, and we subsequently reviewed them together by phone or in a second visit if necessary. A written DVS story assures that each patient understands and confronts the extent of disability caused by symptomatic vitreous opacities (SVO), before making a final decision to accept the small but definite risk of treatment, similar to that attending removal of cataract opacities.

DVS stories, correlated with a vitreoretinal surgeon’s examination confirming the responsible vitreous opacities, are the best possible indicator for the appropriateness of curative surgery. For after all measurements of visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, quantitative ultrasounds, and quality of life, it is still THE PATIENT’S DETAILED SYMPTOMS that are most appropriately actionable.

Kalen Swanson, (a retired social worker and psychotherapist who herself suffered from DVS before vitrectomy) and I recently reviewed a collection of “floater stories” written by patients who were found on examination to have extensive vitreous opacities consistent with DVS. In a separate essay we describe typical DVS symptoms, and she details the psychological impact of DVS.

Click the button below to read 28 floater stories – one selected for each year I’ve been treating DVS patients. Read on and gain a better understanding of their predicament and of the frustrations endured by too many, for too long.

![]()

All patients were treated at Retina Specialists of Alabama in Birmingham, Alabama, USA. RSA is pleased to assist the Helen Keller Foundation for Research and Education in providing this informational website.

Vitreoretinal surgeons treating Degenerative Vitreous Syndrome (DVS or extensive floaters) at RSA include:

Drs. Robert Morris, Mathew Sapp, Matthew Oltmanns, and Matthew West.

Dr. Robert Morris

Dr. Mathew Sapp

Dr. Matthew Oltmanns